Has all the recent news about SPACs left you wondering what all the fuss is about? Special Purpose Acquisition Companies, or SPACs, aren’t new; they’ve been around for decades. But over the past year or two, they’ve become an increasingly popular way for private companies to go public.

Do SPACs have a place in your portfolio? We see two ways you might feel about them:

- Thanks, but no thanks. At Vista, we have nothing against private ventures. But long story short, they don’t fit into our disciplined investment strategy. Before they go public, SPACs are inherently speculative, and there is no way to assign them to an underlying asset class. Once a company has gone public, whether it originated from a traditional IPO, direct exchange, or SPAC is irrelevant to how we position it in our globally diversified portfolios.

- Got it. But out of curiosity, what are they? We’re glad you asked! We’re always fascinated by the intricacies of how our brilliant capital markets operate—SPACs included—and are delighted to share more insights on how they fit into the bigger picture.

Three Paths for Going Public

Why go public to begin with (i.e., offer company shares to the general public, who then become stakeholders)? If a privately held company is chugging right along, there may be no need. Going public is expensive and labor intensive, adding layers of burdensome regulation and costs, while founders give up an element of control to fellow shareholders.

But if a business is ready to reach a higher level, going public may be just the ticket to ride. A successful initial public offering (IPO) can raise capital to accelerate growth, pay down debts, and/or fund an exit strategy for existing owners. It may also attract new business through increased public awareness.

There are essentially three main ways to take a company public: a traditional IPO, a direct listing, and a SPAC transaction.

Initial Public Offerings

IPOs are the most familiar approach for going public. They’re also the most costly and time-consuming, with a lot of logistical and regulatory hoops to leap through. In a traditional IPO, a company hires an underwriter, typically a large bank, who provides legal paperwork, pricing, and marketing support. When the company is nearly ready to go public, they and their underwriter usually go on a road show, reaching out to big, institutional investors and other deep-pocket possibilities. The goal is to garner support for the offering, while discovering a realistic share price for the launch.

It’s worth mentioning, IPOs require a lockout period, or a set time frame (typically the first 180 days), during which existing shareholders are not allowed to sell any of their positions. IPOs also provide for a greenshoe option, which allows a company to sell more shares than agreed upon if there’s particularly strong demand (which can create additional dilution among existing shareholders).

Direct Listings

If a company does not want or cannot afford an underwriter, they can list their shares and sell them directly on an exchange. Direct listings are a quicker and much more cost-effective way to go public. However, there is one big caveat: The company does not create and offer any new shares. It lists only existing shares already held by employees, private investors, and similar stakeholders. This means a company cannot raise any new capital through a direct listing. While the current shareholders do not face dilution, they also do not have the expertise provided by underwriters. They can miss out on opportunities and safeguards, which a company could utilize with an underwritten offering.

Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs)

SPACs are also often called “blank check” companies or “reverse mergers.” SPAC founders create a shell company, which they then list on an exchange. Investors can then buy shell company shares, often without knowing exactly which private company the founders are targeting to acquire.

Because this process occurs before the targeted company goes public, this method is almost purely to raise capital and is, in turn, purely speculative. When someone purchases SPAC shares, their money sits in an interest-paying trust. The SPAC founders then typically have about two years to either make an acquisition or liquidate the shell company and return investors’ capital. Upon going public, the shell company shares automatically convert into the now-public company shares.

While this process doesn’t include an underwritten offering of new shares, SPAC founders typically seek guidance from experienced underwriters and big institutions. This alleviates the level of dilution that occurs in traditional IPOs. In other words, the transaction becomes more exclusive. If big-name underwriters and high-end traders do hop on board, it often negates the need for a common road show and can fetch higher prices than a traditional IPO. Also, when the shares go public, their price is already effectively set, with less worry that a volatile opening market day might upset the IPO apple cart. (Traditional IPO shares are often priced the night prior to going public.)

SPACs Attack

To reiterate, SPACs are highly speculative in nature. Participants often don’t even know the industry, let alone the specific company they are potentially buying into, and outcomes run the gamut—from big wins to woeful losses, to a return of capital in what effectively served as a low-interest savings account.

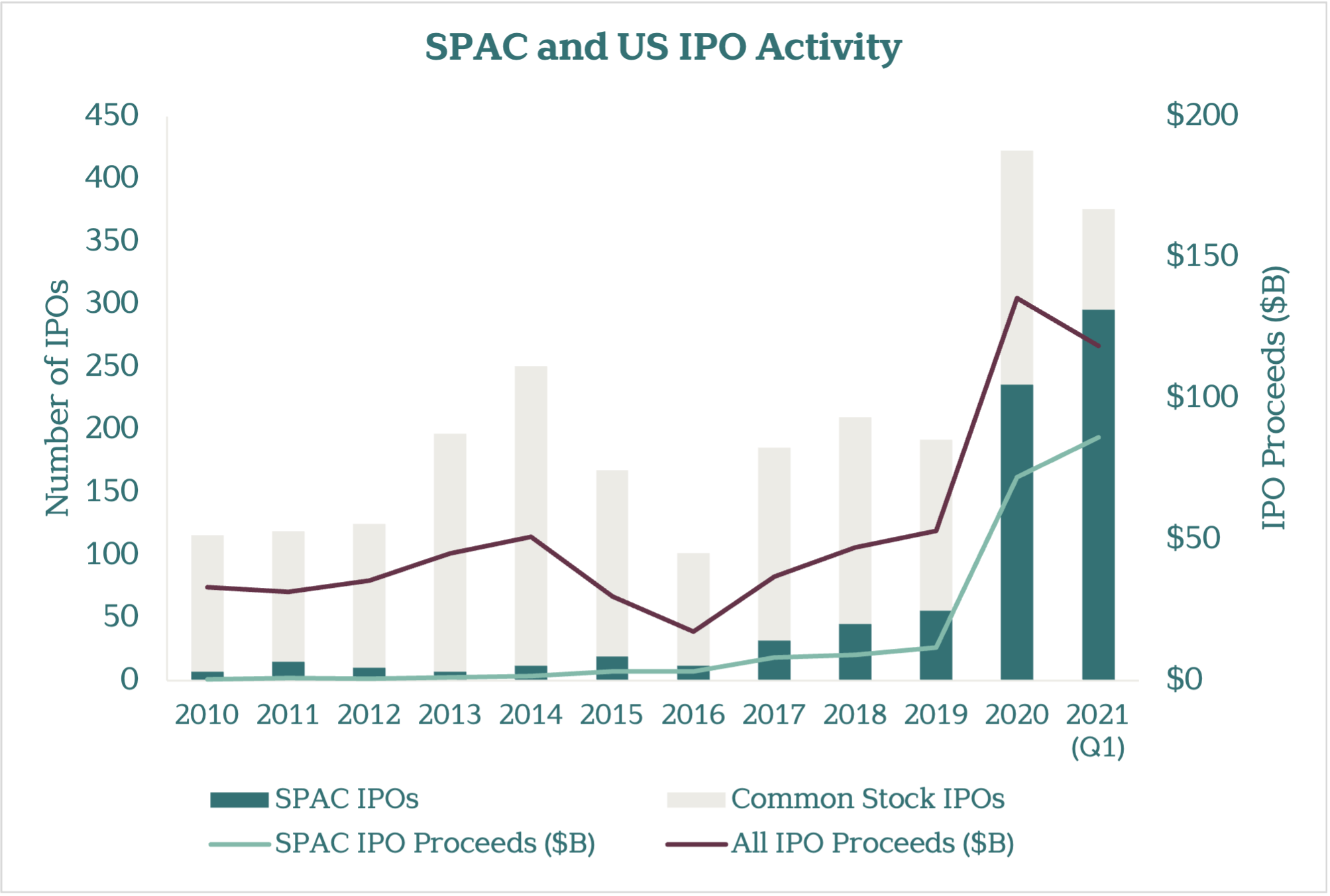

And yet, as the following illustration clearly shows, SPACs have been surging lately, overtaking traditional IPOs as a path of choice for companies seeking to raise significant capital to fund their operations. Their popularity skyrocketed to more than half of market share in 2020, with nearly 250 SPACs going public and corresponding proceeds totaling more than $80 billion.

Source: Dimensional using Bloomberg data. Sample includes all US common stock and SPAC IPOs with a minimum offering price of $5 for which data is available. Dimensional Fund Advisors LP is an investment advisor registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Why So Many SPACs (and What’s It to You)?

What explains the recent surge in SPACs? There are a number of possibilities:

- Trading Frenzies: Perhaps more individual traders have been craving to get in on the action—for better or worse. SPACs are more speculative than traditional IPOs (which are speculative enough already!), and are cheaper and easier to stage. This may appeal to some.

- Economic Awakening: Perhaps the exuberance of a re-emerging, post-lockdown economy is leading the charge.

- Pandemic Adjustments: Maybe it was because traditional IPO road shows simply weren’t feasible for most of 2020–2021, making SPACs a practical alternative.

- Market Mania: During a relatively long run of upwardly mobile markets, investors may be forgetting real trading risks remain, especially among concentrated bets and private ventures.

Likely, it is a combination of all these possibilities, and more. Regardless, will SPACs remain the dominant force for taking companies public, or are they destined to lose their current steam? Time will tell. In fact, it seems like interest in SPACs may already be cooling due to investors’ seemingly increased sensitivity to overpricing. SPAC IPOs dropped down to 63 in the second quarter of 2021, compared to a staggering 298 in Q1 2021. [Source]

What about investing in IPOs or private company stock in general? For example, we Oregonians love our Dutch Bros coffee. We even sport bumper stickers saying so. But does that make Dutch Bros a hot investment, now that it’s filed to go public? In a word, no. But the explanation deserves a post of its own. Look for that soon, or give us a call if you’d rather not wait to learn more.