With the recent calendar-year downturn in the stock market and the Fed’s aggressive rate hikes to combat inflation, some investors are worried about a looming recession and its potential effects on capital markets.

About half of U.S. economists surveyed recently believe we’ll see a recession by the end of 20231.

Should we worry about a recession?

A Primer on Recessions

Both recessions and market downturns are unpredictable in the most literal sense of the word—they cannot be predicted. But history offers valuable insights into recessions.

Since 1926, there have been 15 recessions, lasting thirteen months, on average.

A recession is defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) as “a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and lasts more than a few months.” The NBER uses a variety of indicators to identify peaks and troughs in the business cycle, such as personal consumption and income data, employment rates, and gross domestic product growth.

Of those 15 recessions, six were not associated with a bear market for stocks—defined as a 20% or more decline. And of the 20 historical bear markets, 11 have not been associated with a recession.

Suffice it to say, one doesn’t guarantee the other.

Perfect Timing vs. Discipline

While no one knows where markets will head in the short run, we do know that staying invested has paid off more than trying to time investment decisions in response to recessions.

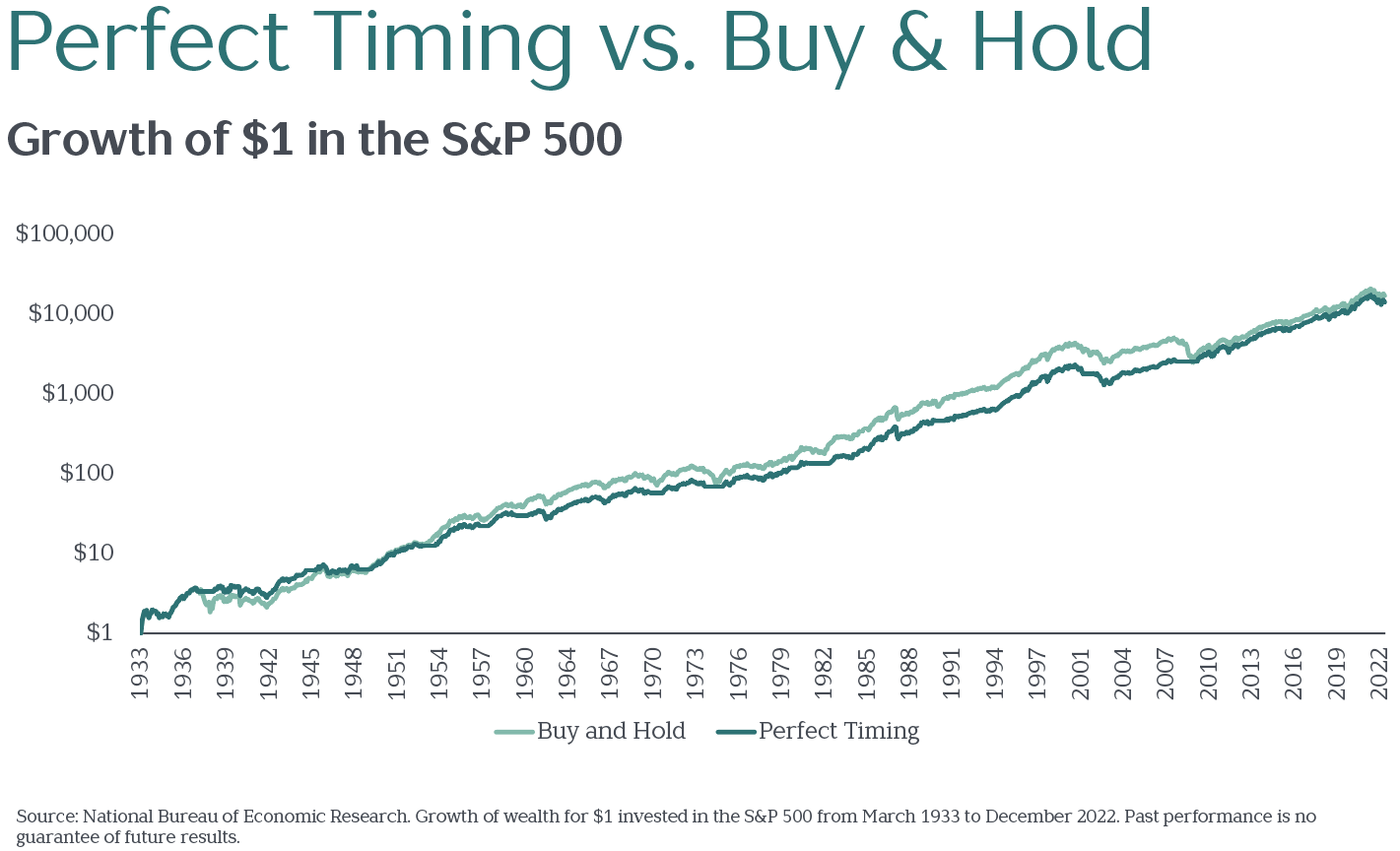

Consider a buy-and-hold approach. If you were to have invested $1 at the start 1933, always reinvested dividends, and never sold, that dollar would have grown to more than $17,000 by the end of 2022.

That same dollar invested using a “perfect timing” strategy—which we’re defining as getting out of stocks at the onset of a recession and only reinvesting once a recession had ended—would only have grown to $14,161.

You read that correctly: Despite getting out of the stock market in advance of recessions and getting back in as soon as they ended, the “perfect timing” strategy actually performed worse than a disciplined, “buy-and-hold” approach.

How can this be?

Investing in a Recession

Markets are forward-looking, meaning current prices reflect market participants’ expectations for the future. Last year’s stock declines may indicate a recession is looming, but that doesn’t mean markets will continue to fall from here.

In 14 of the past 15 recessions, the stock market bottomed out months before the trough in economic activity. That’s right, stock prices began rising from their lows even while the economy was still in recession.

The average gain from the stock market’s lows to the end of past recessions? About 30%.

Of course, peaks and troughs in economic activity are not identified until many months after they’ve occurred. It’s taken about fifteen months, on average, for the NBER to announce these turning points in the economy. And by that time, stock prices have been even higher.

In fact, by the time the NBER has issued what many people interpret as the “all clear” sign that a recession has ended, stocks have already risen by an average of 65% from their lows.

Manage Risk, Minimize Worry

Our takeaway? Reacting to a recession—rather than the recession itself—is the true cause for worry.

Instead of trying to predict the next recession, sensible investors accept that market downturns—whatever their cause—can strike without warning.

The best preparation for investing in a recession is to construct a well-diversified stock portfolio complemented with an appropriate amount of safe bonds.

That, and a healthy dose of discipline.

—–

1Harriet Torry and Anthony DeBarros. “Economists in WSJ Survey Still See Recession This Year Despite Easing Inflation.” The Wall Street Journal. January 15, 2023. Economists in WSJ Survey Still See Recession This Year Despite Easing Inflation – WSJ