With fewer than five months to go until Election Day, this election year is already shaping up as a bit more unusual than most.

There’s a rematch between presidential candidates for only the seventh time in U.S. history. We’re expecting an “epic wave” of retirements in Congress. And a host of other factors—including stubborn inflation, high interest rates, and global conflicts—could raise more questions than answers from candidates as election day draws closer.

One question voters will have for certain: “How much will the election impact the stock market and, ultimately, my investments?” It may be reassuring to know this question arises even in the most humdrum of election seasons—and that history tells us the answer is not as much as you might think.

Markets Don’t Follow Party Lines

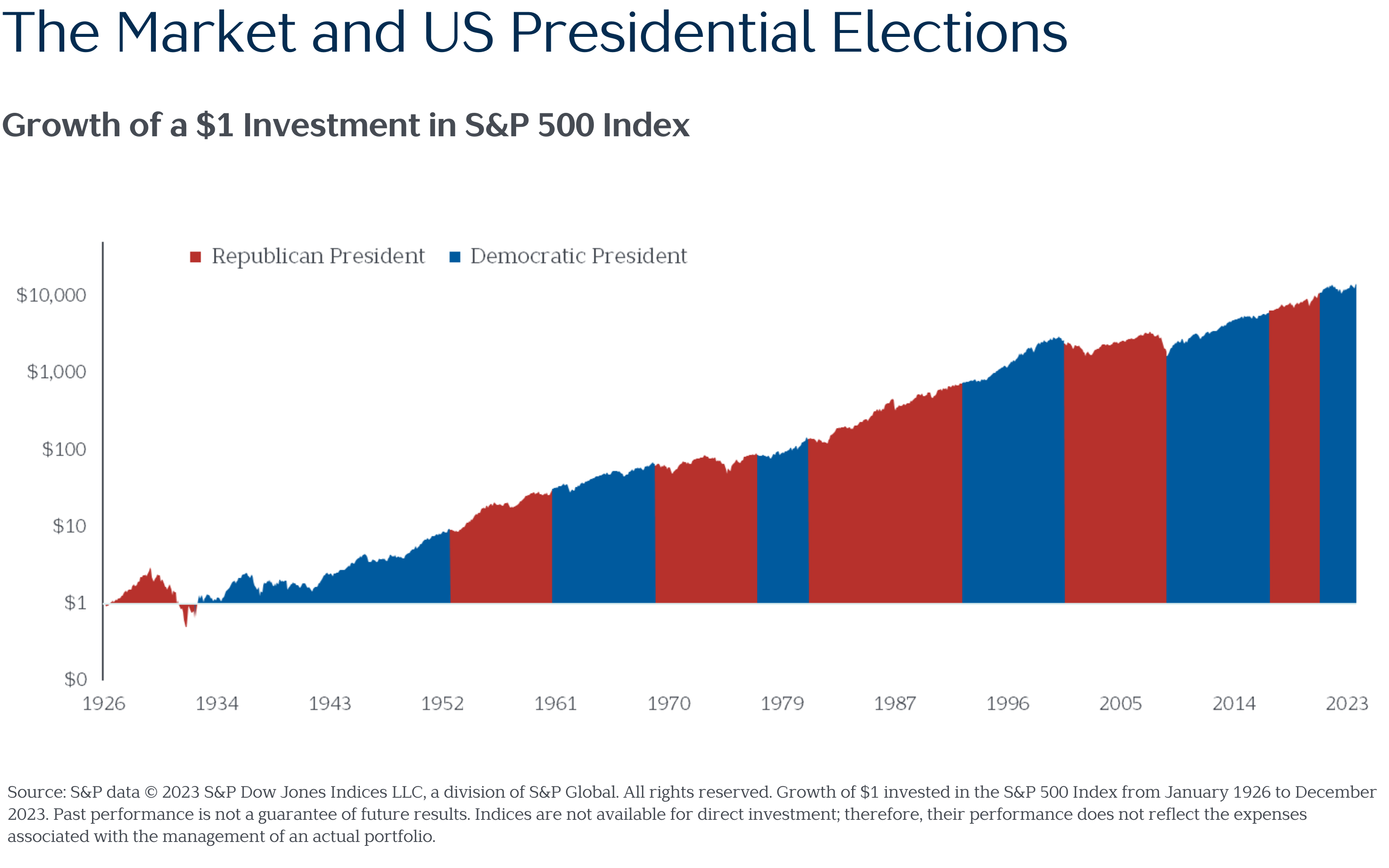

It’s natural for investors to look for a connection between who’s in charge of our country and stock market performance. But nearly a century of data tells a different story. From 1926 to 2023, the S&P 500 Index has had a steady upward trajectory despite a fairly even split between Democrats and Republicans in the White House.

Why is this? First, presidents don’t have as much influence on economies or markets as they often claim (or deny, depending on the economic climate). This isn’t to say they have no effect; after all, presidents appoint policymakers, set the tone for foreign relations, and sign or veto bills into law. But our checks-and-balances system dilutes a president’s direct impact on how our economy and markets perform.

Second, shareholders are investing in companies focused on serving their customers and growing their businesses regardless of who is in the White House. U.S. presidents may have some impact on market returns, but so do many other factors—the actions of foreign leaders, interest rate changes, changing oil prices, and technological advances, just to name a few.

Busting Common Myths

It’s easy to fall prey to the myth that stock markets move based on election results. That’s what the headlines would have us believe, anyway.

Many myths have taken root because politicians and pundits make both promises and predictions—and they often state them as fact. However, we can dispel these myths by examining recent data. For example:

Myth: Financial publications accurately forecast future market performance.

The truth is that analysts and editors at publications don’t have a crystal ball. Some of them predicted a drop in the stock market in the days immediately following the 2016 election. Instead, markets experienced a significant jump.

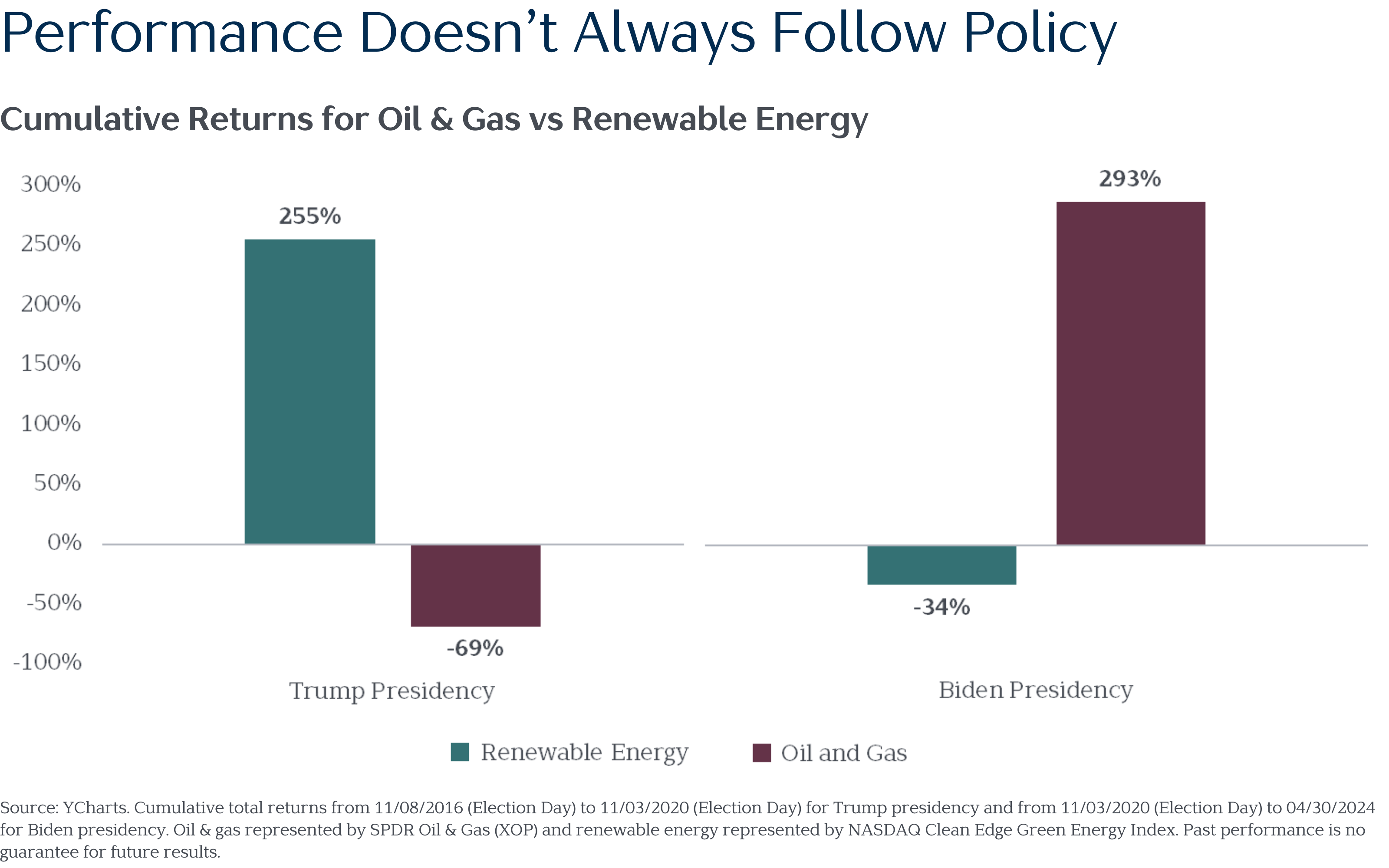

Myth: Certain sectors always thrive under one party’s policies.

Sectors can appreciate or depreciate no matter which party is in the White House. Democrats tend toward favorable renewable energy policies, while Republicans lean toward support for the oil and gas industry. Yet the oil and gas sector declined under Trump and has grown during the Biden administration.

Myth: Volatility increases in the months leading up to an election.

Although it may certainly feel that way, the data doesn’t agree. A Vanguard study of presidential elections between 1984 and 2020 showed that fluctuations in the market are similar in the days before the election to any other time. Vanguard’s research also indicated that returns during presidential election years and non-election years are statistically indistinguishable.

Hail to Investing Basics

The takeaway? Our elected officials have some influence on market performance, as they determine policy, establish regulations, and appoint economic decision-makers. However, politicians and policies are only two factors among a host of factors affecting market performance.

While the governing party can influence the economy and markets, election results should not dictate your investment decisions.

Markets don’t reward investors for electing the “correct” political party. Instead, markets reward investors for discipline, patience, and consistency. Your portfolio is constructed to weather all market environments and provide the returns you seek, even during election seasons.