It’s worrisome, to say the least, to read headlines referencing a potential default by the U.S. government on its debt obligations.

For those unfamiliar with the nation’s debt ceiling history, we thought it would be helpful to provide some perspective on this important aspect of the government’s authority to pay its bills.

What is the debt ceiling?

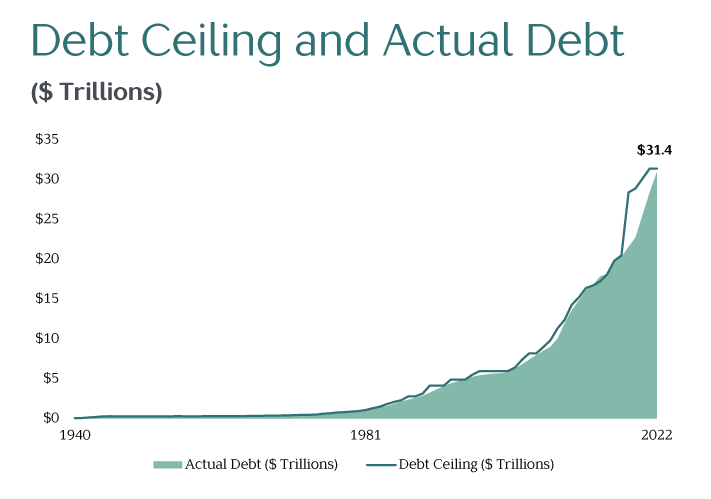

The debt ceiling, or debt limit, is a restriction set by Congress on the amount of federal debt the government can accrue. While the government has bills to pay, the debt ceiling limits the amount the U.S. Treasury can borrow to pay for the nation’s bills and future investments. The current debt limit is $31.4 trillion.

Why is this relevant now?

In January 2023, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen informed Congress in January the Treasury had begun using “extraordinary measures,” as U.S. outstanding debt neared the debt ceiling.

Extraordinary measures are authorities used by the Treasury to prevent the U.S. from defaulting on its obligations as Congress deliberates on increasing the debt limit. These extraordinary measures primarily involve the suspension of investing in new, or reinvesting the proceeds of maturing, government securities.

Recent headlines suggesting the U.S. might “default” has led to worries amongst the public.

Is this debt “crisis” new?

Since the aggregate debt limit was created back in 1939, it has been lifted on nearly 100 occasions—nine times in the last 10 years. Many previous instances were preceded by similar political posturing and predictions of financial disaster.

On each of these past occasions, however, a deal was reached to raise the debt limit and pull our government from the brink – often at the eleventh hour.

To illustrate just how close Congress has cut it in the past, in 1979 a resolution was passed so late the payment schedule on a portion of short-dated Treasury Bills was missed. The incident was quickly resolved, but technically represented a default.

What happens if a resolution to raise the debt limit isn’t reached?

If the debt ceiling is hit, the amount of outstanding debt cannot be increased by the federal government. Existing debt (think: U.S. Treasury bonds) would not necessarily go into default, contrary to some media reports. Government revenue still far outpaces the amount needed for interest payments (more than 5 ½ times as of year-end 2022).

While difficult decisions would have to be made about which U.S. obligations to pay, the Treasury would likely prioritize debt services, Social Security and Medicare, and certain defense payments over other types of spending.

What are the potential consequences of default?

A default would likely cause significant, albeit unpredictable, damage to the domestic and global economy. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has been quoted as saying it would be “devastating” for the U.S. financial system and could lead to another “global financial crisis.”

Much of the world relies on a strong U.S. economy—U.S. Treasury debt is the world’s benchmark safe asset and acts as the basis for the pricing of many financial products and transactions around the globe, and the U.S. dollar is considered the world’s reserve currency.

If Congress does not increase the debt ceiling, the U.S. credit rating would likely be downgraded, potentially leading to an increase in interest rates for many consumer loans.

When U.S. sovereign debt was downgraded from AAA to AA+ after the 2011 debt ceiling impasse, however, U.S. Treasury yields actually declined as investors sought the perceived relative safety of U.S. Treasuries as other global economies suffered in the aftermath of the global financial crisis.

Have past impasses related to the debt ceiling negatively impacted markets?

While economic and political uncertainty have often led to higher market volatility, there does not appear to be a meaningful difference in stock market returns in the months before and after a resolution to raise the debt ceiling.

In the six months preceding a past increase in the debt ceiling, price returns for the S&P 500 have averaged 4.2%. In the six months following a decision to raise the debt ceiling, returns have averaged 3.8%. Neither figure is statistically different from the 4.4% average return for all six-month periods evaluated from March 1954 through June 2022.

No one can say with certainty what the short-term future holds. We do believe, however, that a prudent investment strategy should be based, in part, on lessons learned from periods of past turmoil and not based on pure speculation about the future.

Markets appear to be anticipating yet another last-minute debt limit deal. Stock and bond prices are higher now, as the deadline nears, than they were earlier in the year. The information baked into market prices, as conveyed by millions of investors with real money at stake, would seem more reliable than the politically charged statements coming out of Washington.

With that in mind, we continue to believe a diversified portfolio consisting of nearly every publicly traded stock and real estate investment in the world and anchored with government bonds—issued not only by the world’s most productive economy (The United States) but complemented with the highest quality bonds from the world’s most credit-worthy countries—remains the most effective protection against uncertainty.