It has been a tough year to be an investor, with nearly every asset class around the world taking its lumps.

With a globally diversified, balanced stock and bond portfolio down nearly 20%, it’s tough to find a silver lining. The reality is, it could be worse.

Consider the brokerage accounts of those who jumped on the Bitcoin bandwagon after it surged 61% in 2021. The cryptocurrency has plunged 65% from those lofty 2021 heights.

Or the speculators who flocked to “meme” stocks GameStop (GME) and AMC Entertainment (AMC), after performance soared heading into last year’s holiday season. Down 42% and 80%, respectively, from a year ago, oversized helpings of the two chat-board darlings have likely made mincemeat of portfolios.

While many investors likely avoided the siren song of crypto and meme stocks, not many can say they resisted the temptation of the popular “FAANG” stocks. After all, these five stocks alone accounted for nearly 18% of the entire market capitalization of the S&P 500 Index at year-end 2021.

“FAANG” is the catchy acronym for tech titans Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, and Google. In the ten years ending 2020, the megacap FAANG stocks returned 14% more per year than the U.S. stock market as a whole. After a long run of such remarkable performance, it’s not hard to imagine many investors answering “yes” to the very natural question they asked themselves: Shouldn’t I own more of that?

Unfortunately, when investors load up on high-priced, growth-oriented stocks—whether individually or through funds focused on those popular sectors—they’re only investing in their uncertain future performance, not their impressive past record.

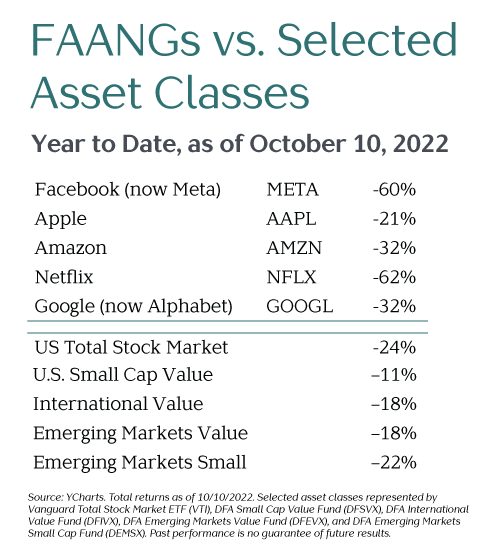

And 2022 has not been kind to the FAANGs, neither in absolute terms nor relative to less popular (but important!) asset classes such as small cap and value stocks.

Viewed through the lens of history, the FAANGs’ performance woes shouldn’t be all that surprising. Impressive returns are what push companies to become the market’s biggest stocks. But once a stock has “arrived,” it has been harder for company results to continue surprising the market with not just good news, but even better-than-expected news that drives prices higher.

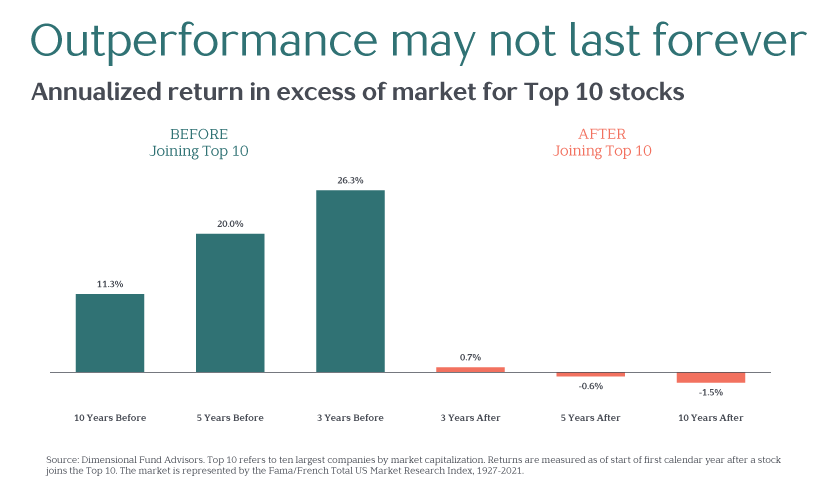

Consider the Top 10 U.S. stocks by market cap, from 1927–2021. On average, and over nearly a century, members of this elite group delivered average annualized returns that were more than 26% higher than the market in the three-year run-up to becoming a Top 10 stock.

But then, in the three years after their arrival at the top, their performance edge shrunk to less than 1% per year, on average. After five years, that advantage was wiped out and they underperformed the overall stock market. As the graphic below shows, the underperformance gap grew even wider over 10 years following their ascension.

Intel is an illustrative example. In the decade before it became a Top 10 stock, Intel posted annualized returns that were 29% more than the market’s return. You read that right: returns of 30% more per year for ten years! In the decade following, however, Intel underperformed the broad market by nearly 6% per year.

What can we learn from Intel and these other past top performers? Clearly, the winning stocks of yesteryear aren’t all the winning stocks of tomorrow. But it’s also exceedingly difficult to predict which ones will be, or when that change in performance leadership will occur.

This is why we diversify, first and foremost, by spreading assets across thousands of stocks in a variety of market sizes and styles, spread among industries and geographies. Yes, we know this means we don’t get to pile into today’s hot stocks and their huge past returns. At times, that can feel uncomfortable, but we diversify anyway.

That’s also why we rebalance, repeatedly trimming allocations that have been outperforming and using the proceeds to replenish underweight positions. Even though rebalancing adheres to the investment ideal of “buying low, selling high,” it often feels like prudishly removing the punch bowl from the party. It’s unpopular, but we do it anyway.

Diversifying broadly. Intentional portfolio construction, including small cap and value stocks. Disciplined rebalancing. These are key elements of our efforts to protect and grow our clients’ piggy banks.

Sure, these simple aspects of investing may not deliver positive returns this year or huge gains in any other year. They won’t deliver the thrills of riding the crypto and chat room waves, and they’re not as charming as the market’s current heavyweights in the cocktail chatter department.

But they have helped prevent a bad year from being much, much worse.