After a decade-plus global market growth spurt, it’s been awhile since disciplined investors have had many opportunities to engage in tax-loss harvesting.

That was before COVID-19. Suddenly, like a desert after a downpour, tax-loss harvesting “season” is in full bloom.

As with any thorny subject, however, not every investor should seize every opportunity. When does it make sense to engage in tax-loss harvesting, and when might it be best to leave it alone?

Tax-Loss Harvesting in Action

Do you hold any stock or fund shares in your taxable accounts that are currently worth less than you paid for them? If so, you can sell the shares at a loss, and then promptly reinvest the proceeds in a similar (but not identical) replacement holding. This keeps you fully invested in the market. After at least 31 days have passed, you can optionally complete a “round trip” by selling the replacement shares and repurchasing the original position.1

Once the losses are harvested (again, from taxable accounts only), you can use them to offset realized gains and up to $3,000 of ordinary income on your current tax return.2 You can also “store” leftover losses to use on future returns. In short: Tax-loss harvesting helps you realize capital losses for tax-planning purposes, while leaving your portfolio’s asset allocation unchanged.

That’s tax-loss harvesting in theory. But before you start harvesting every loss you can find, let’s cover a few practical realities.

Tax-Loss Harvesting Is a Deferral, Not a Free Pass

One common misperception is that tax-loss harvesting erases taxable capital gains. In reality, it usually defers rather than eliminates them. How so? When you engage in tax-loss harvesting, you almost certainly end up lowering the basis of your harvested holding. Unless you can later donate or bequeath the holding intact (or it fails to ever appreciate), this eventually comes to roost as a higher taxable capital gain when you sell the asset.

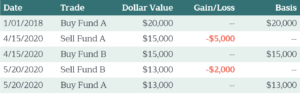

Say you purchased shares of Fund A for $20,000 in January 2018. Today, your holding is worth $15,000. You sell Fund A to harvest the $5,000 loss and buy a similar Fund B with your $15,000. After 31 days, Fund B has dropped still further to $13,000. You complete the round trip by selling Fund B and repurchasing Fund A.

Exhibit 1: A Tax-Loss Harvesting Illustration

So far, so good. By buying the similar Fund B during the 31-day waiting period, your asset allocation stayed essentially unaltered, and you now have a total $7,000 loss you can use to reduce your tax bill in 2020 or beyond.

However, your investment’s cost basis also dropped by $7,000, from $20,000 to $13,000.

Fast-forward 30 years to 2050. The holding is at $60,000, and it’s time to sell it for real. The taxable gain you’ll incur will be $47,000 ($60,000 minus a $13,000 cost basis), or $7,000 more than it would have been had you not lowered its cost basis from $20,000 to $13,000 during your tax-loss harvesting days.

In other words, you didn’t eliminate the taxable gain; you deferred it.

The Cost of a Tax-Loss Harvest

Tax-loss harvesting also has its cost complexities. For example, there’s no sense incurring $20 in round-trip transaction fees to harvest a $20 loss. Plus, markets are messy. In our simplified example, Fund A and Fund B happened to decline further.

Since values had declined after a month, no problem. But what if prices had instead surged? To (ideally) sell Fund B and reinvest in Fund A, you’d have to incur a taxable, short-term gain, which can negate the tax-saving benefits of the initial loss. This is why we want to make sure the initial loss is large enough to create a buffer in case Fund B appreciates over the 31 days it is held.

In some cases, depending on the appreciation of Fund B, you might prefer to hold onto the replacement security rather than swap back to the original. As a result, it’s important to pick your replacement carefully—in case it becomes a lasting investment.

Bottom line, tax-loss harvesting requires careful tending.

Thoughtful Tax-Loss Harvesting

Now that we’ve covered the theory and reality of tax-loss harvesting, let’s circle back to its potential benefits. Through thoughtful tax-loss harvesting, we aim to help our clients reduce their tax bills in down markets and potentially in the years thereafter. We may also be able to use a loss to offset a gain they might otherwise be reluctant to incur (such as unwinding a concentrated, appreciated position), without wreaking havoc on their tax bill.

Whether the logistics of tax-loss harvesting actually make sense for any particular client depends on a variety of personal, financial, and family factors. Before, during, and long after the harvest happens, we must integrate the move into clients’ broader wealth plans.

So, is it tax-loss harvesting season for you? We are here to help you sort out the cost-saving facts from the potentially costly fiction.

Notes

1. The “similar but not identical” and 31-day waiting period guidelines are in place to avoid violating the IRS’s “wash sale rule,” which would prohibit you from claiming a tax deduction on the loss as described.

2. $3,000 ordinary income on a married-filing-jointly return; $1,500 if single or married filing single.