Over the past decade, index funds have taken in nearly $1.5 trillion of investor assets. These dollars have flowed primarily from actively-managed funds, which have witnessed withdrawals of more than $1 trillion.

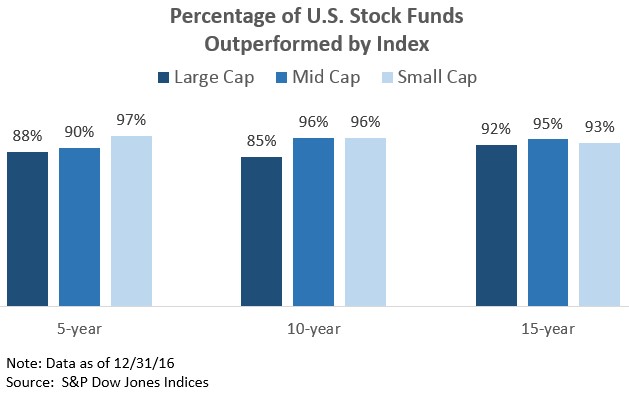

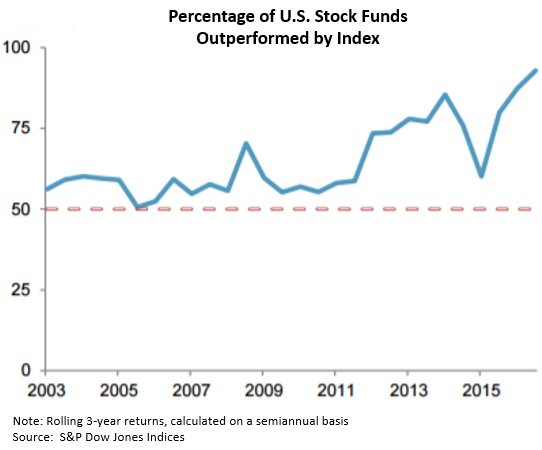

What was once derided as unfashionable “folly,” passive investing—aka indexing—has become quite popular. And why shouldn’t it? Indexing is a highly effective investment strategy—easy to understand, inexpensive and has delivered reliable long-term results. Very few actively-managed funds, in fact, have kept pace with the performance of index funds over the past fifteen years.

Indexing’s rising popularity, however, has caused some to question its future. Has indexing gotten too big? Will indexing—and markets—break down if more and more investors adopt the strategy?

We’re not concerned, for a few reasons:

Index funds in name only

Behind much of the growth in indexing has been the proliferation of exchange-traded funds (ETFs). In the past two years alone, more than 500 new ETFs have come to market. While technically index funds, many bear no resemblance to the truly passive index funds for which firms like Vanguard are known.

There’s now a global water index fund, a 3D printing index fund, an index fund focused on companies run by founder CEO’s (with the clever ticker symbol BOSS) and one tracking the 38 companies that make up the long-term care index (ticker: OLD).

Remarkably, there even exist leveraged index funds, which promise to pay two- or three-times the daily return of an underlying basket of stocks. With whom are such funds most popular? Active traders seeking to supercharge their bets on the short-term direction of the market.

So long as these “index funds” continue capturing investors’ assets, there’s no reason to worry about buy-and-hold indexing getting too big.

Fewer sheep to fleece

But what if it does get too big? Should the growth in truly passive index funds continue, it may become even more difficult for the remaining active investors to outperform.

Remember, active investing is a zero-sum game—winning investors only do so at the expense of losing investors. Thus, a shrinking pool of active investors may have a harder time finding “easy pickings.” Evidence from the past 15+ years certainly suggests so:

Consider that 50 years ago, less than 20% of all assets were professionally managed. Today, that figure is closer to 70%, meaning the pros are no longer competing with regular Joe’s, but with other professionals.

Outperformance is exceedingly difficult when the competition is so good.

World peace, unity of religion and indexing

Despite their incredible merits, index funds are unlikely to become too popular. In fact, it’s hard to even imagine a world in which “everybody indexes.”

Consider just a few of the many factors that differentiate investors: age, appetite for risk, investment goals (home purchase, retirement, pension obligations), personal and/or organizational values, policy constraints, geographical biases.

It’s simply not possible for every investor to hold the same portfolio of index funds. A world free from wars and in which everyone shared the same religious beliefs seems more plausible!

But what if they did? Unrealistic as it is, securities prices could certainly deviate from their “true” values making markets less efficient. And if securities became mispriced, it would clearly pay for informed investors to abandon indexing. By taking advantage of mispriced securities, however, informed traders drive prices closer to their true values, thus helping

to restore market efficiency.

Back to reality

Let’s not forget investors are humans. We are hard wired to believe we are better than average, and we love nothing more than investments that have fared well in the recent past. Combined, these traits trick us into believing we can pick market-beating investments in the future.

But when markets struggle at some point in the future, just as they’ve done in the past, certain investors will be dissatisfied with indexing’s “market average” return. Pained by temporary losses, they may abandon indexing in pursuit of whatever active strategy has done well at that time, only to find that outperformance in active investing rarely persists.

Rather than worry about indexing becoming too popular, investors should remember the rewards of investing are most often reaped by those who remain committed to a sensible and reliable strategy—regardless of how unpopular it once was or how fashionable it has become.